Embracing the paradox of Being:

A relational view of

epistemology,

ontology,

logic and difference.

Let’s get right to it, shall we?

With respect to ontology, let us say that there is no “it,” no independent reality that is exclusive of the observer. This is a basic insight from second-order cybernetics: the observer must always be included in the observed. Despite this, of course, we do have much talk and thinking about “it” that does not take the observer into account—we are very interested in the “what” of the universe, but have a fairly difficult time illuminating our own nature. But this is okay, because ultimately the talk about “it,” the pointing to “it,” (not the thought of the “it” itself) is more fundamental to “it” than anything else, because it is the relations that are primary. We can say that thingness is a subset of relatedness. Following Eugene Gendlin’s (1997, p. 22) process-concept of “interaction-first,” we can conceive of relations not as forming between two already-existing “things,” but rather as being recursively self-generated between other relations. In this sense, things are the precipitate of relations, a hardening out of a more fluid state.

Going further than Gendlin, we can take a cue from the process-language of alchemy (Miller, 2008) to see how relations themselves are a precipitate of the tension between complementarily opposing potentials, made by a distinction out of the whole. This corresponds to the recursive ontological alchemical sequencing of the elements from Fire (the whole) to Air (polarity) to Water (relation) to Earth (thing), to Fire (a new, transformed whole). Relations are to opposing potentials of a distinction as things are to relations. Opposing potentials are themselves a precipitate of the whole by virtue of distinction (of Fire by Fire), and work alongside each other within the whole simultaneously. Each step from the whole is a kind of step-down transformation; ontologically we could say that beginning with level N, we move to level N-1. Each level is pulled out of simultaneity by an act of distinction within the whole, of the whole, by the whole. A cascading of levels of distinction thus yields the ontology of “things.”

This ontological movement is balanced by an epistemological one, which works in the complementary direction. In alchemy, the recursive ontological sequence from Fire to Earth becomes the recursive epistemological sequence that moves from Earth to Fire. That is, the way in which we transform our knowing moves from the initial things or facts (Earth; made by our distinctions), to their relations (Water), to the contexts of the relations (Air), to the whole of the integrated contexts (Fire), which finally yields new facts (a new, transformed Earth). The pattern of our knowing follows the ontological pattern of coming-into-being as a kind of inversion of it, which is why Goethean-style observation is central to the spiritual science of anthroposophy: it seeks to bring to conscious awareness the patterns through which the objects of our perception form. The cascading of levels of distinction thus yields not only an ontology of “things,” but simultaneously an epistemology of knowing activity, which together yield the whole of cosmology.

Here is a “kind” of solution: embrace the paradox. We need not think of “being” as absolute; neither must it be purely “constructed.” There can be both a transcendent and immanent aspect to “being” simultaneously. Epistemology rests upon ontology, but ontology likewise rests upon epistemology. They are recursively united in a “unitas multiplex,” a complex unity. How we know limits reality, and reality limits what we know. But this is not a circle all at the same level; it is part of a spiraling loop that moves beyond itself while referring to itself; it transcends itself at a higher level while being fully itself at the lower level (transcendence + immanence). It is paradox in action as an expression of a higher patterning of “truth,” the truth that paradox is simultaneously the end-stage of logic, and the beginning of something else.This can be approached in another way. We can begin first with a problem of the modern condition, made apparent most strongly by both postmodernism and deconstructionism. The problem is that language is relative, and all notices of difference are relative and contextual. More strongly, our whole epistemology therefore becomes relative and contextual. From this perspective, how can we reconcile “being” and the need for an ontological grounding of a “reality” if all our knowledge is already, in a de-facto way, arbitrarily founded? Do we have to sacrifice our ontological ideals on the altar of a tattered epistemology, shredded always at the edges by the inability of language and knowledge to reach being? Must we abandon, as Kant would have us do, any claims of knowledge of higher realms? What do we do about the chicken and egg paradox, wherein all claims about ontology arise first from an inherent epistemology (which in postmodern thought can only be a relative epistemology), when it would seem logical that some ontology must give rise to the system which can yield that very epistemology in the first place? Must our epistemology be forever and absolutely divorced from ontology (the Kantian dilemma). No!

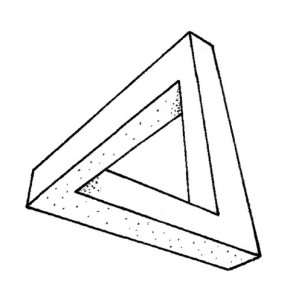

Indeed, paradox is the only possible foundational center for (and infinitely distant periphery for) logic. This is because from a second-order (process) level, no logical system can logically justify itself—only we, as whole human beings (that think, feel, and will) can do that. To do so we may invent a new, better, more complete or complex logical system, but then that system too must be justified as well. Thus at the very heart of logic is the paradox of the a-logicality of logic. Gödel famously approached a similar idea in a formal way in his two incompleteness theorems in 1931, which show that any logical system robust enough to even accomplish basic arithmetic will have logical implications which are true within the system but which the system cannot prove to be true.

Indeed, paradox is the only possible foundational center for (and infinitely distant periphery for) logic. This is because from a second-order (process) level, no logical system can logically justify itself—only we, as whole human beings (that think, feel, and will) can do that. To do so we may invent a new, better, more complete or complex logical system, but then that system too must be justified as well. Thus at the very heart of logic is the paradox of the a-logicality of logic. Gödel famously approached a similar idea in a formal way in his two incompleteness theorems in 1931, which show that any logical system robust enough to even accomplish basic arithmetic will have logical implications which are true within the system but which the system cannot prove to be true.

Paradoxical relationships thus serve as the bounding limits for what can be called “logical”; they limit the form of thinking which stays within those bounds… but they simultaneously mark the exit points for thinking, like huge signs on the map saying “here be dragons” that beg for exploration. Paradox is thus a key entryway for any thinking that wishes to see the nature of the dragon for itself, rather than to be content with its “impossible” description.

The dragon “itself” is “impossible” because it a fantastical/metaphorical creature, and thus its description likewise partakes of the very same impossibility – how can one describe accurately that which is non-existent? Thus all descriptions of “dragons” are themselves a kind of paradox. But this is seen only from the perspective of the second-order. The first-order content is merely the description of the dragon. But this first-order content of the description is seen, from the second-order level of process, to lead one to the very nature of the second-order itself as a paradoxical loop functioning as a potential in the first order. It is only from the second-order that the paradoxical nature of the first-order is seen as a potential (for something new, different, other). This recognition is only possible from the second-order perspective in actuality, not abstractly as a thought-content on its own (these words here won’t necessarily accomplish this for you, although they might). Thus, paradoxically, the first-order content holds the potential for an awakening to the second-order process which illuminates how the first-order content made the actuality of this awakening in fact. This paradoxical relationship between the first and second-orders holds as a general pattern, and leads towards the realization of how the second-order relates to the first: the second order is immanent in the first, while transcending it. This same relationship holds between ontology and epistemology, but in a slightly different way: mutually.

This is all to say that paradox signals the point at which logic ceases, while indicating at the same time that human thinking is not bound by logic—only logical thinking is thus bound. Human capacities transcend and include logic. The reason for reason always lies beyond mere reason. Stated differently, logic always only applies to thoughts, not to thinking. Logic is a limitation of the form of thinking, not of the process of thinking itself, and it is thus that human thinking is free of logic: it may bind itself by logical forms, but is not required to do so.

What is human thinking that moves through and beyond logic? One way to approach this is through what Rudolf Steiner (1994) calls Imagination. This is the first step beyond logic as the highest arbiter of thinking, but it does not obviate logic—it merely places logic within a larger framework of the potentials for thinking as a whole. Imaginative thinking allows for thoughts which are living, but it is precisely this living aspect which cannot be expressed within purely logical formations of language: it cannot be reduced to a specific form any more than one would expect an exacting and thorough description of a seed, written on a piece of paper and placed in soil, to actually grow into a plant.

So: being can be usefully approached with the help of the distinction between levels of order. We must constantly resist the urge to reify and ontologically project our thoughts into a realm that is categorically static and dead, as if the Parmenidean dream of ultimate ontological unity had always been (necessarily) true. We must not make the assumption that our thoughts of things necessitates the thing’s own being (a collapse of the paradoxical dynamic between ontology and epistemology). Rather, we can recognize a co-creative act whereby the being of the thing and our thinking about it constitute a unity that has a second-order cybernetic character: its unfolding as a thing and as an idea are co-created; they are part of the same distinction. This insight is fundamental. For example the “being” of a spoon—its ontology—is never separable from the thinking by which the spoon arose—in the first place in the mind of the creator of the spoon, and secondly, as an inward enlivening of the same idea in a new context in the person now thinking about the spoon. It is quite strictly correct to say that “there is no spoon.” But this relationship has consequences far beyond any such specific example, when it is understood as a foundational pattern for the entirety of the cosmos. It is, indeed, a basis for cosmology. To wit:

So: being can be usefully approached with the help of the distinction between levels of order. We must constantly resist the urge to reify and ontologically project our thoughts into a realm that is categorically static and dead, as if the Parmenidean dream of ultimate ontological unity had always been (necessarily) true. We must not make the assumption that our thoughts of things necessitates the thing’s own being (a collapse of the paradoxical dynamic between ontology and epistemology). Rather, we can recognize a co-creative act whereby the being of the thing and our thinking about it constitute a unity that has a second-order cybernetic character: its unfolding as a thing and as an idea are co-created; they are part of the same distinction. This insight is fundamental. For example the “being” of a spoon—its ontology—is never separable from the thinking by which the spoon arose—in the first place in the mind of the creator of the spoon, and secondly, as an inward enlivening of the same idea in a new context in the person now thinking about the spoon. It is quite strictly correct to say that “there is no spoon.” But this relationship has consequences far beyond any such specific example, when it is understood as a foundational pattern for the entirety of the cosmos. It is, indeed, a basis for cosmology. To wit:

What there “is” is evolving relationships of difference—not a difference OF some thing, as the something is precisely what arises from changing relationships of difference. Things are not things; they are changes in relationships of difference. Or more specifically, changes in relationships of differences of changes in relationships of differences of changes in relationships of differences of…. The epistemology of difference is an ontology of evolution; the ontology of evolution is the epistemology of difference.

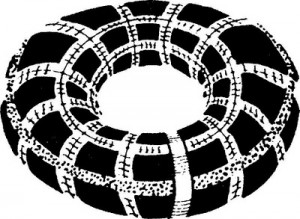

Let me give an example by way of a thought experiment. Imagine a universe that consists entirely of an infinite volume of homogeneous water. The most primary possible differentiation that can be made in the homogenous water is not one of an ontological nature, conceived in the normal sense of the word, because the entirety of the water is homogenous and exactly like the water everywhere else. All we have in this universe is water. We cannot therefore take out some finite volume from the whole to examine it separately, as there is no place to put it that is not already just water; no difference could be noted because this would require another universe, while the current one is stipulated as homogeneous. The most primary possible differentiation in this situation is one of self-movement, and in the case of water the most natural form of self-movement manifests as the formation of a toroid. The toroid “is” the changing of a relationship of difference. It is not enough that there be only a difference (as if the difference itself was static and unchanging), for without the movement—the change of the difference—the toroid would be nothing but the water. The toroid cannot be separated from the water (for water is all it is, and it “is” nothing without water) or otherwise be brought into distinction with the water, without the change of the difference which makes the difference that is changing. The change of the difference is the difference: if the difference ceased its changing then the toroid would become again indistinguishable from the surrounding water. But every difference is also simultaneously a relationship. All polarities are also unities. Thus we can speak not just of a change of difference but more appropriately of a change of a relationship of difference. We can speak of this change as evolutionary, and in this sense can be taken for the basis of both ontology and epistemology simultaneously. Each is the necessary context for the other to (simultaneously, i.e. outside of time) appear.

The ontology of every “thing” is thus paradoxically entwined with the self-differentiation of that which is self-less as an epistemological act. Every “being” is also a “knowing”; every “knowing” is also a “being.” The talk of “essence” in the discipline of ontology has historically been blind to the coincident necessity of an epistemological act of knowing, an act which is itself ontological. Being and Knowing are polar co-arising primal activities as mutually self-defining differences. The “ground of being” is also the “ground of knowing.”

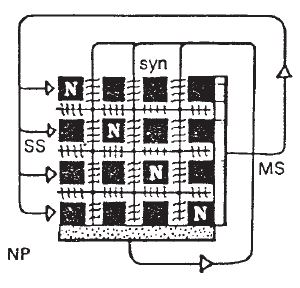

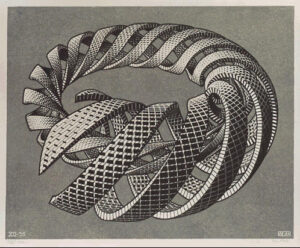

This self-referentiality at the heart of ontology, coincident with the epistemology of difference, is perfectly illustrated by the doubly self-enclosed, self-relating form of the moving toroid of water in an otherwise still volume. Topologically the toroid is formed from the movement of two circles which are oriented orthogonally to each other. Metaphorically we can take one circle as being, the other circle as knowing. This then adds a new layer to the cybernetic move of recursion required between the sensory and motor surfaces in an organism, as indicated by Heinz von Foerster in this diagram from his book Understanding Understanding, where the recursive move is accomplished by twisting the plane topologically into a toroid, so that the sensory and motor systems (thinking and willing, epistemological and ontological) become a single complex whole. (p. 224-225).

|  |  |

The fundamental knowing is a knowing of being, and the fundamental being is a being of knowing. The primal ontological distinction is a primal epistemological distinction. We can say, using this metaphorical language, that the “first difference” is topologically toroidal, with one axis (ontology) coincident and mutually self-defining with respect to the other axis (epistemology). The two together yield what we can call cosmology, which is the playing out of the change of the relationship of differences as the changes of the relationships of differences across all lower orders N-1, N-2 … N-n.

In this perspective, the Divine, rather than being the unmoved mover (à la Aristotle, who had a linear epistemology), is also a self-moving mover (embodying a circular/recursive epistemology). This is an image that humans can share in as we develop towards the higher capacities of our own self-moving (inwardly, as for example in the development of our capacity for freedom). But we must master this freedom through self-limitation; another paradox. The master is self-limiting. This self-limitation takes the form of learning to limit our inward movements along with the changing relationships of difference around us: the wisdom of the world presented to our senses/will (cerebellum), our feeling (limbic), and our thinking (frontal cortex). This is the basis for an aesthetic epistemology.

References

Gendlin, E. (1997). A process model. New York: The Focusing Institute. Retrieved from http://www.focusing.org/process.html

Miller, S. T. (2008). The Elements as an Archetype of Transformation: An Exploration of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire (Thesis). John F. Kennedy University, Pleasant Hill, CA. Available here.

Steiner, R. (1994). Theosophy : An introduction to the spiritual processes in human life and in the cosmos. Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press. Available here.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário